Select a News Item:

Football: Narbonne is City Section title favorite but has lots of challengers -latimes.com

LAUSD coaches work for less than minimum wage, panel hears -latimes.com

La Chancla Still Lives In Highland Park, Los Angeles (NELA)

El Sereno Veterans Monument Dedication

Re-elect Jose Huizar L.A City Council District 14

#NightOnBroadway brings light to downtown L.A.’s historic theaters

Diamond Supply Co. Skate Plaza at Hazard Park

West Coast Anthem - Troublesome Ft. Outwest (Official Video)

"Lola's Love Shack" DVD

USC to bring $1 million in park improvements to Hazard Park

In-Studio: Eric Marty, New ELAC Head Football Coach, 1/28/15

East L.A Community comes together to raise funds for Steven Cruz

"I Can Fly" written by Ronin Gray

Boyle Heights Beat to host L.A. Council District 14 Candidates Forum

Councilmember Jose Huizar kicks off 2015 Campaign in El Sereno

Boyle Heights Community Youth Orchestra

Marco Aguirre True Oregon Duck from East L.A

Mark Gonzales 1986 Model – Vision Skateboards

Maria "Sokie" Quintero for LACC District Board of Trustees

Otomisan: The Last Japanese Restaurant in Boyle Heights -kcet.org

L.A. City Section 2014 All-City Team Selections -eastlasportsscene.com

Teamster Horsemen - Motorcycle Association CH.42 spread Christmas cheer in East L.A

Boyle Heights Winter Wonderland

Transfers bring the titles in high school football today - latimes.com

Football: Stevie Williams is Eastern League player of the year -latimes.com

#cicLAvia Explores SouthLA Leimert Park

Anthony Denham gets the call from the Texans - www.hou.scout.com

Anthony Denham nearly missed his big call - espn.com

#Ferguson Protests continue in Los Angeles #DTLA

East L.A Minor League Football Team to Open Season in January

cicLAvia South L.A 12-7-14

Boyle Heights Shoeshine man with bounce in his step gains a foothold at Union Station - latimes.com

Garfield to Play Narbonne In City Section Semifinals - egpnews.com

Football: Two terrific semifinal games in City Section Division II -latimes.com

UCLA Honors Jackie Robinson by retiring number 42 across all sports - "ucla newsroom"

Boyle Heights Bridge Runners

East L.A College Huskies Football 1974 State Champions 40th Anniversary interview with HC Al Padilla

South Gate takes down South East in Azalea Bowl

Legendary L.A Rivalry - 80th East L.A Classic on ESPN SportsCenter

Anthony Quinn #PopeofBroadway Mural Restoration Kick-off

Self Help Graphics & Art #UnaCitaConLaVida in Boyle Heights

Terrell Goins Interview -South Gate rams 62 Bell Eagles 7

Artist Hugo Romo - Mariachi Plaza in Boyle Heights

Ronin Gray - The Red Dragon EP .. Free Download

South Gate's Lavell Thompson Highlights vs Garfield Bulldogs

Lavell Thompson puts best foot forward at South Gate - latimes.com

Garfield surges past South Gate - latimes.com

Garfield , South Gate to Battle for Eastern League Top Spot - egpnews.com

South Gate ends losing streak , beats Roosevelt 42-19

She can dream , can't she? Cristela a new comedy October 10th on ABC

South Gate Rams roll past Huntington Park Spartans 49-3

Jose Huizar cicLAvia The Heart of LA , Boyle Heights East LA

Joshua Boothby Red Bull's Fixed gear Freestyle Rider at cicLAvia in Boyle Heights

Lincoln Tigers defeat Esteban Torres Toros 40-6

Kenny Washington Memorial Game IV Lincoln Tigers 42 Marshall Barrister 0

South Gate Rams take out Eagle Rock Eagles 48-16

RIP : The Apple iPod , 2001-2014 - latimes.com

Football: Narbonne, South Gate, Bernstein top City Section title contenders -latimes.com

Tony Washington Scores 3 TD's leads South Gate over L.A University 48-14

Salesian Mustang Running back Felipe Meza Post Game Interview vs Muir Mustangs

South Gate Rams Shut Out Westchester Comets 35-0

He's Back "Da Truth" Lavell Thompson #SouthGateRams #UnfinishedBusiness

Torres Toros look to compete in Northern League

Roosevelt Rough Riders take on Grant High Lancers in football scrimmage

Garfield Bulldogs compete with Crenshaw Cougars in scrimmage

Kill Capone Screening at a Theater near you

Anthony Denham Blocks Punt vs Atlanta Falcons

Texans: Denham , Grimes make impact on Special Teams -houstonchronicle.com

Steven Batista Speaks on former teammate Anthony Denham of Houston Texans

Hoping to make Texans cut, Denham knows about survival-houstonchronicle.com

James Shaw III RB/DB South Gate Rams Football "Class of 2016"

El Sereno Stallion Football & Cheer "Meet & Greet" 2014

Diamond Supply Co. Skate Plaza Opens in Hazard Park "Grand Opening Video & Photos"

New Skate Plaza Opens in Hazard Park -boyleheightsbeat.com

Football: South Gate to rely on running back Lavell Thompson -latimes.com

Diamond Supply Co. Public Skate Plaza Grand Opening at Hazard Park in Boyle Heights 7-24 at 5pm

East Los High - Season 2 Now Streaming

Celebrating the Life of Bobby "Babo" Castillo - Dodger,Tiger,Friend

Angelica "Jelly Felix #42 BIO - Lincoln High Tigers - UCLA Bruins Softball

Two New CicLAvia Routes Announced For October and December 2014 -la.streetsblog.org

Garfield Bulldogs at Roosevelt Rough Riders Girls Basketball "Full Game" 2013

#AlumniFootball -Franklin Panthers slip past Eagle Rock Eagle 7-6 "Watch Full Game "

Nick Young agrees to 4-year, $21.5 million deal with Lakers- cbssports.com

#TBT Divinyls I Touch Myself

South Gate High Rams Football Teams Locker Room gets Broken into , We need your Help

Tierra live Saturday July 26th @ Nick's Taste of Texas in Covina CA

Boyle Heights to Rancho Palos Verdes Bike Ride

San Gabriel River Trail/Bike Path

take a Ride! Manhattan Beach to Venice!

4th of July @ Venice Beach

Salesian Crushes Mission Prep in Football Division final 34-0

Lavell Thompson RB "Highlight Reel" South Gate Rams Football 2013

#IBikeLA -> Downtown to La Cienega

I Bike SoCal

Bobby Castillo dies at 59; former Dodger pitcher taught Valenzuela screwball-latimes.com

#AlumniFootball - Roosevelt holds off Garfield 12-6 in 4th Annual #AlumniClassic

Caracol Marketplace - Every First Sunday of the Spring Summer Months

Go Skate Boarding Day Los Angeles 6th St Bridge 2014

#KickStarter #HNDP #MusicTruck Mobile Mentorship To Inspire New Artists

California Classic High School All-Star Game - LA City vs Oakland Bay Area

Boyle Heights Electrical Art Box Project Tour

605 High School Football All-Star Game "Full Game" & Photos

West Wins Down the 605 -midvalleysports.com

ELAC's Dioseline Lopez Signs UCSB National Letter of Intent

Denham's road took him 'to hell and back' -espn.go.com

Texans Rookie Anthony Denham says football helped changed his life -myfoxhouston.com

Boyle Heights Real Estate Flier Stokes Gentrification Fears - scpr.org

Gentri-flyer Sets Off Social Media Storm in Boyle Heights- la.streetblog.org

El Sereno Memorial Day - Honoring Our Veterans

Justice for Gabriel Soto - Memorial March in East LA -ktla.com

Vote Hilda Solis for County Supervisor -June 3rd

Anthony Denham has signed with the Texans as a free agent."

Baseball: El Camino Real is No. 1 seed for City Section Division I playoffs -latimes.com

Softball: El Camino Real is No. 1 seed in City Section Division I - latimes.com

Football: Cathedral is off to fast start in passing tourneys -latimes.com

Mr Belvedere "Complete Series" #TBT #80s

Jennifer Lopez & French Montana – I Luh Ya Papi | Music Video

Ruben Salazar : Manin the Middle - A Documentary by Phillip Rodriguez

Plans for historic Sears Tower spark gentrification debate "Video" boyleheightsbeat.com

El DeBarge - Who's Johnny - Short Circuit - #TBT

ELAC's Aaron Cheatum Signs NLI with Washington St Basketball Program

East L.A College Womans Softball vs Mt SAC Mounties Highlights & Photos

"The Eastsiders" on KLCS-TV channel 58

Richard Montoya's Water & Power Brings New Voice to Cinema - latina.com

V. Stiviano, Disturbing Secret name changes & ties to Boyle Heights Roosevelt High School

Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council Election Results 4-26-14

Esteban Torres Toros Baseball defeat Hollywood Sheiks 4-3

Nick Young & Jordan Farmar throw first pitch at Dodger Game

East LA College Huskies Baseball vs Long Beach City College Highlights Interviews

San Diego PD Enforcers vs LAPD Centurions Charity Football Game

Sway in the Morning featuring Bishop Lamont

El Sereno 4th Annual Kite Festival Ascot Hills

Bus crash: Vigil held for Adrian Castro El Monte High School

Jay Z's Downtown L.A Fest Could Gouge Taxpayers

NELA TV Talks With Franklin’s New Football Coach Narciso Diaz

Lincoln Heights Chamber of Commerce Installation Dinner

#cicLAvia Iconic Wilshire Blvd 4-6-14

Fabian Debora's "Light from Darkness" Mural Dedication M-Bar

Ultimate Warrior Dead at 54 - tmz.com

Gerald "El Gallo Negro" Washington vs Skipp Scott

Skid Row Studios - The Qumran Report

In Studio Show : Erick Huerta Wolfpack Hustle Marathon Crash Ride - www.eastlasportsscene.com

Some concerned about Jay Z event at downtown L.A park - latimes.com

New Sears Tower owner plans to seek community input - www.boyleheightsbeat.com

Scott Pearson Head Coach Warren High School Baseball Interview - Photos Warren vs Franklin Panthers

John Fogerty - Centerfield

Boyle Heights Native Jesus Zesati Captures Basketball State Title

LiL Al Davis Talks Raiders Offseason (#DJaxToOakland, MJD, P.Sims)

Punky Brewster - Punky Brewster's Workout #80s

A Long 5.1 Earthquake Hits La Habra

Boyle Heights getting more Gold Line TOD Action -Building Los Angeles Blog

Eric Garcetti #LAMayor - City Budget 101 in LA's Eastside

L.A Marathon Crash Ride - March 9th, 2014

#Ride4Love Brings Bicyclist together in #Watts

LiL Al Davis - Raiders Offseason 2014 (Matt Schaub & RM Haters)

#BoyleHeightsRising Community Clean Up #2

Maxium Overdrive 1986 Film by Stephen King

LiL Al Davis - (My Take on Free Agency) Raiders 2014 Off Season

Alexander Flatos ATH - South Gate Rams Football Senior Highlight Film 'Class of 2014"

The East Los All-Stars featuring Power Play Band at Stevens Steak House

Snap Hold & Kick Football Camp comes to Inner City

Kenny Washington Groundbreaking Pioneer in the integration of professional football gets his Square

Anthony Denham - 2014 NFL Combine Results : Tight ends run the 40-yard dash -sportingnews.com

Kenny Washington paved way for black players in NFL - washingtonpost.com

Kenny Washington Square Dedication at Lincoln High School

Interview with Sticky Rick , Godfather of the L.A Art Sticker Scene -lataco.com

California Gas could reach $4 a gallon in a month

Michael Jordan Turns 51

Narciso Diaz New Football Head Coach at Franklin High School in Highland Park

Boyle Heights Community #CD14CleanUp with Jose Huizar

The Eastsiders : A Documentary Celebrating of The Eastside of Los Angeles from 1920-1965

"Ride 4 Love" East Side Riders Bike Club - February 15th in Watts

Will.i.am gives Big Shout Out to Roosevelt Rough Riders on Arsenio -rooseveltlausd.org

I Love Tito's Tacos !

ELAC Track Hall of Fame : 5 Individuals , 1 Team Inducted -wavenewspapers.com

New Construction Set for Lorena Plaza in Boyle Heights

Gold Line Adjacent Affordable Housing in Boyle Heights

The Phone Call: #InWithTheNew RadioShack Commercial (official version)

Disorderlies "Starring the Fat Boys" 1987 "Full Movie"

The Zoot Suit Riots

Day On Broadway 6th Anniversary Bringing Back Broadway

Snoop Dogg like you've never seen him before

Painted Utility Boxes Move West to Downtown's 'Indian Alley' -kcet.org

LADOT Planning 40 Miles of New Bike Lanes this Year - laist.com

Ice Cube Gets Gangsta On 'Goodnight Moon'

Los Angeles Olympic Murals (The Restoration of Glenna Avila's LA Freeway Kids)

Nick Young Upset No Lakers Teammates Defended him in Fight with Alex Len

Happy 85th Birthday to Martin Luther King Jr

Boyle Heights Community comes together for #EvergreenJoggingPath Clean up

Bringing Back Broadway

East Side Bike Club -Slow Es Cool Iconic East Side Bike Ride- Jan 5th

Zamora Bros in East L.A Suffers Fire Damage on Christmas Day

A Christmas eve tale about why coaches coach - latimes.com

Changing the Cycle - East Side Riders Bike Club

The Best of Culture Clash

Lincoln Heights 10th Annual Holiday Parade & Festival

Winter Wonderland comes to East LA Civic Center #EastLAOnIce

Bellator MMA, KOTC Vetaran Joe Camacho Dead of Apparent Heart Attack at Age 41

Crenshaw takes down Narbonne in Division 1 City Final

San Fernando tops South Gate with late drive -wavenewspapers.com

#6 South Gate takes on #1 San Fernando in Div2 Final

The Thrill of making a Championship Game #SouthGateRams - latimes.com

South Gate edges Granada Hills to reach Div2 Title Game-wavenewspapers.com

Surprising South Gate reaches City Section Div2 Final - latimes.com

#CIFLACS Football Final Four results - www.lacitysports.com

Utah Utes vs USC Trojans PAC 12 Football- eastlasportsscene.com

L.A Cty Sports Semifinal Football Predictions

Salesian hoping third time is a charm - wavenewspapers.com

Torres Faces View Park Prep in Division 3 Semifinals - wavenewspapers.com

South Gate One Win from City Division ll Final - wavenewspapes.com

Chatsworth, South Gate emerge as Surprise City Div2 Semifinalist Teams

South Gate Knocks Off Unbeaten Eagle Rock 30-7 in Div2 Quarterfinals

South Gate takes on unbeaten Eagle Rock -wavenewspapers.com

#6 South Gate Rams @ #3 Eagle Rock Eagles - friday 7pm

Coach Orgeron Front-Runner for USC Job? wavenewspapers.com

Love on San Pedro #SkidRow

Elite 8 #CIFLACS Predictions - LACitySports.com

T-Birds Upset #8 Bobcats 22-14

USC vs Stanford #Unfiltered

Defense Sparks Dorsey Victory Over Roosevelt -wavenewspapers.com

LACitySports.com City Section Football Results Round 1

ELAC Huskies take down Compton

#6 South Gate 62 #11 Lincoln Tigers 22

LA City Section Football Playoffs Predictions - LACitySports.com

Montebello Tops Schurr 14-7 to Win League Championship

Batman vs Superman Football Brawl @ East L.A College

Los Angeles City Section Football Playoff Seeding Div1 ,Div2 & Div3

Its A Classic Bulldog '4-Peat' www.egpnews.com

Moses Saucedo Honorary Captain for the Garfield Bulldogs

South East holds on to beat South Gate 36-28 in Azalea bowl

Dia De Los Muertos in Boyle Heights

Jose Casagran Head Coach South Gate High Rams Football - Regular Season Recap 2013

Wyche Decommits from USC, Commits to Miami

Mister Cartoon Teams with Los Angeles Kings

the i.am.angel foundation Opens College Track in Boyle Heights

Batman vs Superman takes over L.A Football Stadium

Batman vs Superman Movie to start Shooting at East L.A College

Roosevelt Remains Unbeaten by Racing Past South Gate -wavenewspaper.com

Vote! Bad Azz Burrito -Small Business - Big Game

South Gate Rams @ Roosevelt Rough Riders friday 7pm

cicLAvia - Heart of L.A

El Sereno Holds Skate Deck Art WorkShop & Art Show

ELAC Huskies Fall to Southwestern College 35-10

South Gate 51, Huntington Park 37

Best Skate Lessons 2013 - Soul Skating Los Angeles

Malabar Street Elementary Centennial Celebration 1913-2013

Huskies fall to Mt San Jacinto College

SUU defeats Northern Colorado, improves to 4-1

South Gate 50 LA Jordan 6

JV Football - Whittier Christian at Salesian Mustangs

Souther Utah Stuns Sacramento State in Overtime

East LA Beats West LA in Overtime 21-20

South Gate Shuts Out Franklin 14-0

San Jose State Football To Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month

Clark Emerges as explosive Option for Syracuse

Boyle Heights School to Mark Centennial egpnews.com

Salesian routes Hanford West 50-12

Locke Wins on Hail Mary Pass -wavenewspapers.com

Defensive injuries hurt South Gate in 30-28 loss to Locke

Roosevelt defeats El Camino Real 37- 13

Cantu Earns National Honor

Weingart Stadium Opens ELAC Garden

Near Perfect Opening T-Birds Shut Out Fort Lweis in Home Opener

L.A Valley rolls past East L.A College 59-34

University Wildcats hold on and beat South Gate

Boyle Heights Series Premiere Full Episode

Anthony Denham vs Utah St 2013

Pasadena Muir beats Salesian 18-12 in Overtime

David Arriaga lifts Roosevelt to Win Over Fairfax www.latimes.com

Westchester Falls to South Gate 41-0 www.dailybreeze.com

T-Birds Shock Jaguars In Opener www.suutirds.com

City Council Adopts Mural Ordinance

ELAC Huskies showcase new talent in Green & White Scrimmage 2013

South Gate Rams Host Football Scrimmage 2013

Venice Beach Skate Park

Belmont Hilltoppers Escape with 7-6 Win over Garfield Bulldogs #AlumniFootball

L.A Neighborhood Tries to Change,but Avoids the Pitfalls www.nytimes.com

Inside Out Project at Mariachi Plaza

Anaheim Monster Energy Dub Show Tour 2013

Grand Opening Ceremony at Boyle Heights City Hall

Rookie 101 : Jeremy Harris - Jacksonville Jaguars

National Night Out in Boyle Heights Hollenbeck 2013

X-Games Leave Los Angeles

Aaron Cantu heads into Southern Utah camp as No.1 Quarterback

Aaron Cantu gets #1 Spot heading into Fall Camp for Southern Utah

SoCal Spartans Route Inland Empire Meerkats 72-0

Boyle Heights Wolfpack Founder Nissim Leon Awarded at City Hall

South Gate Rams Football #ItsTime2013

Cambridge Scooter Kids , Skate Park , Las Vegas

Celebrating Nelson Mandela Day in L.A - Unveiling Mural in Venice by David Flores

USC Trojans Land ELAC Huskie Future Star Michael Wyche

A "Sneak Peek " Inside Nick Young's Sneaker Closet #NiceKicks

Ronnie Alvarez in new Boost Mobile Subway Pickpocket Commercial

Mark Gonzales - #VisionStreetWear #TheOriginal #VisionSkateBoards #80s #TBT

Donnie Battle, founder and CEO, of 4TH and INCHES Donnie, also former Defensive End player, at ELAC

How are Skateboard Graphics Made? "Featuring Kenny McBride"

Belmont HillToppers hold off Roosevelt Rough Riders 21-20 #AlumniFootball 2013

O.J. Mayo to Bucks: Milwaukee Reportedly Signs SG to 3-Year Deal

State Farm Insurance -Bill Sampson "Guillermo" Marketing Coordinator

Belvedere Skate Park in East Los Angeles

Rest in Peace -Robert Soto .6-30-80-11-13-95

Belvedere Skate Park - East L.A 6-29-13

Kill Kapone - Official Trailer

Go Skate Boarding Day 2013 @ Belvedere Skate Park in East L.A

Mescalito -Said and Done: The Blurry Journey

Salem Red Sox Pitcher found refuge from East L.A on Baseball Diamond

10 Year Old Sebastien De La Cruz Sings National Anthem @Game 3 NBA Finals

Diamondbacks vs Dodgers Brawl -Full Video

East Los High - Watch New Episodes!

UCLA Faces Tuberculosis Outbreak in Skid Row

Donyae Olton ELAC Huskies Football- Exit Interview 2013

What is GENTRIFICATION? Highland Park, Echo Park, Silver Lake, Eagle Rock...

The Toxic Avenger #TBT

Still USC (Still D.R.E. parody)

In Loving Memory of Gabriel Soto #33

El Sereno Memorial Day Tribute "Honoring Our Veterans"

El Sereno Holds Skate Deck Art & Design WorkShop

Cathedral Phantoms Win ELAC Huskie Shoot Out

Armando Gonzalez : The Skate ShopKeeper

East Los High launching June 3rd

Silk Screen Printing with Coffee -Self Help Graphics

Boyle Heights Community Youth Orchestra - Spring Concert 2013

Sixth Street Viaduct Replacement Project Public Meeting

Santa Fe 3751 Steams through El Monte Station

Jacksonville Jaguars select ELAC's Jeremy Harris in Seventh Round of NFL Draft

Cantu shines, White team thrashes Red at Spring football game

WKRP in Cincinnati featuring Sparky Anderson

cicLAvia to the Sea Draws Huge Crowds

Lou Adler inducted in 2013 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

'42' The Real Life Story of Jackie Robinson, Baseball Legend

Hollenbeck Middle School Celebrating 100 years of Educational Excellence

CicLAvia to the Sea

Cyndi Lauper - The Goonies "R" Good Enough

Lincoln Tigers hold on to defeat Belmont HillToppers in Alumni Football Game

POWELL PERALTA / Rip the Ripper Art Show

East L.A Youth Football Team Banned From Local Park

MUJERES DE MAIZ 16th Anniversary Live Art Show

Emanuel Pleitez Exit Speech at the M-Bar in Boyle Heights

East L.A Bobcats hold Community Picnic

East L.A Interchange

L.A. mayoral candidate Emanuel Pleitez is a man on the run

Founder Of East LA’s El Tepeyac Restaurant Was ‘An Absolute Legend’

Manuel Rojas, owner of Boyle Heights landmark El Tepeyac, dies at 79

J.A.K. - Rooftops (Produced By Colby Evans) OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO

Dodger Blue - Hu$tle Height$ - Official Music Video

Newcomer of the Year -- Marqus Valenzuela, San Gabriel, Jr., QB

Hugo A. Romo Chicano Artist from East Los Angeles

Adam Polanco - QB/DE Highlights -Rosemead Rebels -Pee Wee Div- 2012

Soul Skating Los Angeles in Boyle Heights part of growing movement in the inner-city

ESPN 30 for 30 You Don't Know Bo

Bishop Lamont presents...The Congregation EP - Now Available on I-Tunes

Artist Robert Vargas touches up his Mural "Mariachi Vargas" in Boyle Heights

ELAC Huskie QB Aaron Cantu signs letter of intent to play at Southern Utah University

Ramona Gardens 2nd Annual Holiday Toy Giveaway

East Los Angeles on Ice brings Excitement to Community

Downtown on Ice @ Pershing Square

31st "Miracle on 1st Street " Hollenbeck Youth Center in Boyle Heights

Broken parking meter no free ride

5 Effects Obamacare Will Have on Working Americans

Merry Grinchmas "Universal Studios Hollywood"

SoCal Burgers Hold Annual Classic Car Show & Xmas Toy Drive

RIP- Jenni Rivera

L.A Street Car ?

East Side Metro Transit Oriented Development Community Meeting

Narbonne rolls to City title

San Fernando defeats Canoga Park 42-35 in Div final

Anthony Figueroa Highlights Jr Year -Whittier High School Cardinals 2012

Salesian Boys & Girls Club hold Annual Thanksgiving Dinner

Nick & Ricky Wong Football Highlights - San Gabriel High Matadors

San Fernando takes down South Gate 55-27

Skid Row's Unkal Bean

El Tepeyac Cafe holds car wash for Rafael Aguilar

Boyle Heights Farmers Market

Water is Life - The M Bar

ELAC ends football season on final play

El Sereno Veterans Day Tribute

Plaque stolen from Boyle Heights veterans memorial - latimes.com

South Gate rallies to upset Verdugo Hills 55-35

Barack Obama 2012

L.A City Section Div 1 & 2 Playoffs

Huskies Beat Compton College 48-27

Dia de los Muertos on the East Side

Family dispute in Boyle Heights leaves two dead, one in custody

El Tepeyac Cafe on Man vs Food

Thee Mr Duran Show

Huskies move past Chaffey College 40-27

Dwight Howard pays visit to Hollenbeck Youth center in Boyle Heights

Garfield shutouts out Roosevelt in East L.A. Classic

Roosevelt and Garfield gear up for East L.A. Classic football game

Bobcats face Tuff test vs Montebello Indians

Huskies come up short vs San Bernardino Valley College

Largest bus station west of Chicago' opens Sunday in El Monte

Futuristic design chosen as winner of Sixth Street Bridge competition

Cathedral holds off & beats St Paul

Boyle Heights Wolfpack Win Big vs East L.A Bobcats

Endeavour Space Shuttle In South Central Los Angeles

Incumbents Lose Seats,New Faces Win Big at Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council Elections-lastreetblog

Huskies get back on track with win over Victor Valley College

Bell takes advantage of South Gate Turnovers

Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council Candidates introduce themselves

CicLAvia -LA's biggest block party rolls through Mariachi Plaza

Bell Gardens Sweeps East L.A

Espacio 1839 opens in Boyle Heights

Gas prices in California rise to another new record

Garfield hands South Gate its second loss

ELAC Football loses Cantu and game vs Southwestern College 35-26 -elaccampusnews.com

Roosevelt Runs Past South Gate 49-7

Welcome to Farmers Field

South Gate-Roosevelt tops Eastern League slate -wavenewspapers.com

Football: Six unbeaten teams left in the L.A City Section

ELA Bobcats get past Lincoln Heights Tigers & Whittier Redskins

Huskies suffer tuff loss against Mt San Jacinto 35-32

South Gate wins league opener 44-28 over Huntington Park

Sixth Street Viaduct Replacement Project - Design Animation

Steve Sabol dies at age 69

East L.A Bobcats Sweep Huntington Park Spartans in Opener

East L.A Beats West L.A in Shoot Out 58-55

Record Setting Day for Cantu

Long Beach Millikan Rams Lose Late Lead In Thriller vs South Gate

QB Eddie Flores leads South Gate to fourth consecutive win

South Gate football is enjoying a revival

East LA Huskies College Football "Players of the Week"

South Gate keeps intensity up in practice

ELAC Huskies come from behind to beat Santa Barbara College 28-27

South Gate Holds on to Beat Locke Saints 34-24

Historic Boyle Hotel Cummings Block Grand Opening

Ovarian Psycos present Clitoral Mass 2012 - After Party * 2 Year Anniversary

ELAC Huskies take down L.A Valley 40-13

Adrian Cabada ELAC Football O-Line

Los Altos Conquerors run past Salesian Mustangs 48-34

South Gate Routes Santee 42-7

SoCal Burgers in East L.A "Classic Car Nights"

South Gate gets win in coaching return for Jose Casagran

Huskies Compete in Green & White Scrimmage

South Gate Rams Host Football Scrimmage

KLCS 2012 Eastern League Football Preview

BHTYC- 6th Annual Community Awards Gala

Huskies begin full contact

Carlos Lozano heads into camp for Utes ksl.com

Hollenbeck's National Night Out 2012

South Gate Rams look to prove critics wrong

Medwood represents Belize in London wavenewspaper.com

L.A Taco Fest 2012

Scott Pearson is leaving L.A. Cathedral to coach at Warren

Garfield's Saucedo makes a name for himself

Ovarian Psycos present-Tour de la Heights 2012

Hollywood Stars get past South Bay Spartans 29-8

SoCal Smash defeat San Diego Silveracks 42-8

Tanabata Festival in Boyle Heights

Gingee "Rhythm Inside Me"

Chantry Flat Adventure!

Growing Up the Hard Way: Jeremy Aguilar's Success Story

Ben Davidson dies at 72; Oakland Raider

Ted Review by Olusheyi Banjo

Victor Murillo -Rest In Peace

The Beat Junkies – For The Record (Documentary)

Boyle Heights Wolfpack Host Coaches Clinic @ East L.A College

X-Games 18 Los Angeles

Anime Expo Summer 2012

Dodger Stadium Express - Ride Metro!

TAP Card Now Good for Transit on LA City Buses

Blunts & Brewski

Rodney King, key figure in LA riots, dies at 47

Suspected DUI Driver Charged in Deadly Taco Truck Crash

Skid Row “Operation Healthy Streets” begins tomorrow

Marching for Peace

Boyle Heights Farmers Market & El Merkado Negro present CaminArte 6-8-12

East Side Spirit & Pride 1st Annual Ernest Moreno Golf & Luncheon Fundraiser

Former USC AD Garrett hired by Oklahoma school

Bad to Worse in Skid Row

A Memorial Tribute Honoring Our Veterans & George Cabrera Sr WWII Veteran

After 30 Years, a Boyle Heights Intersection Gets a Traffic Light- lastreetblog.com

Metro to force riders to pay on Purple and Red lines by Dec. 1 - latimes.com

HNDP Partners up with the Boyle Heights Technology Youth Center

CASA 0101 Presents The 2012 9th Annual Reel Rasquache Art & Film Festival

Roller Coaster Day @ Six Flags Magic Mountain

CaminArte - Boyle Heights Farmers Market 5-11-12

Dodgers Slugg past San Francisco Giants

51Lou Show aka LiL Al Davis

7th annual Edelbrock Rev'ved Up 4 Kids Car Show

East L.A. Interchange Documentary

Los Angeles Civil Unrest: 20 Years Later-South LA Rises: Community Fair and Rally

Ronin Gray - Triple O

In Memory of John Henry Elorriaga

Romero, Blue Jays winners against Royals

Occupamos! People's Mic Fundraiser @ Tierra de la Culebra

L.A Riots 20 Years Later

Rickey Thenarse takes over at L.A Jordan

National Record Store Day

Tupac Live 2012 At Coachella

About 100,000 cyclists and pedestrians participate in Ciclavia

Boyle Heights Wolfpack Annual Softball Tournament 2012

Expo Line Opens April 28th

Bye Bye, Big Buy

Romero's dominant showing paces Blue Jays

cicLAvia April 15th 2012

Dodger Blue - Dodger Town "Video Promo"

Dodgers beat Padres in Opener 5-3

Arencibia's homer in 16th wins historic opener

East L.A. has a permanent spot in pitcher Ricky Romero’s heart - boyleheightsbeat.com

East L.A's Whittier Blvd gets Beautification

Advanced Screening of "Lola's Love Shack" & Pat's 40th BDAy!!!

Alumni Football USA - Lincoln Tigers Claw Huntington Park Spartans

Community meeting discusses findings on alcohol-related crime, deaths - boyleheightsbeat.com

Are Streetcars Coming Back to Los Angeles?

Torres Leads Garfield past Roosevelt 26-6 in 2nd Annual East L.A Alumni Classic

Nick Young Traded to Lob City

Join Boyle Heights Contingent for L.A. Marathon Crash Ride

The Ovarian-Psycos Bicycle Brigade Make a Space for Women on the Eastside la.streetsblog.org

Sorry, small business — liquor stores can increase crime

Garfield prepares for Alumni Classic

R.I.P Whitney Houston

Kid Ink - Time Of Your Life [Official Lyrics Video]

WIZ KHALIFA FEAT SNOOP DOGG WILD VIDEO

Long Hidden Historic Façade of Clifton’s Brookdale Cafeteria Revealed

American Me Documentary

ELAC's Carlos Lozano signs with Utah

Corazon Del Pueblo BBQ Fundraiser at Solidarity Ink!

Boyle Heights: Past, Present & Future

Roosevelt Football 2011 Highlight Teaser

"2 Comma Kidd "

New South Gate Football Head Coach Jose Casagran meets & greets student athletes

Ricky Romero Keeps it Real!

East L.A Alumni Classic set for March 10th

Snoop Dogg wins over $72,000 on 'The Price is Right'

get to know the Ovarian Psycos

Asante named St. Paul head football coach - foxsportswest.com

Ronin Gray -The Takeover- Now on I-Tunes

L.A.'s historic 1st Street bridge reopens after 3-year closure -latimes.com

Tamale Fest 2011- Salesian Boys & Girls Club - City Terrace

Hip Hop Showcase Vol.2- The M Bar

Sout East Jaguar Jonathan Santos on NBC's "The Challenge"

Robert Lewis named L.A City Div 2 Player of the Year

Duarte Skate Park

South Gate High Football Hires Jose Casagran as Head Coach

Occupy L.A. cost city $2.3 million; most of that will boost budget deficit - latimes.com

Boyle Heights Bike Lanes Go Green

Womens Basketball- Huskies defeat L.A Southwest 82-54

Get that Work Out Inn!

L.A City Div. II: South East 51, Marshall 34 ESPN.com:

San Diego Metro Transit System "Trolley"

Coastal rail projects get $21 million in federal grants

Carson knocks off Garfield 24-7

Cantu leads ELAC to bowl victory - wavenewspaper.com

RIP - Robert Soto -6/30/80-11/13/95

ELA Rollin Out 2011 Classic Charity Car Show & Toy Drive -

Alumni Football USA- South Gate hangs on to beat South East in Overtime 11-8

Huskies 5-0 in Mountain Conference ,beat San Benandino

Gremlin Div- Bobcats advance to Championship beating Covina vikings

Midget Div- Duarte Hawks too much for Bobcats

Peewee Div- Rosemead Rebels comeback to beat Montebello Indians

Jr Peewee Div- East LA Bobcats get past Covina Vikings & head to Championship

Photography by Rafael Cardenas & Paintings by Fabian Debora

Roosevelt suffers 14-0 loss to Bell

Modern span will replace historic downtown L.A. bridge

East L.A Bobcats advance to Semi-Finals

Huskies beat Compton College win Mountain Conference

Jr Midget div- Wolfpack runs past Baldwin Park Road Runners

Garfield holds on to beat Roosevelt in Classic

East L.A Classic Press Conference

Garfield Bulldogs Practice 11-2-11

Huskies keep streak alive vs Victor Valley College

Garfield Breezes past Huntington Park

The Harvest Festival -Boyle Heights 2nd Annual Pumpkin Patch

Midget Div- East LA Bobcats take down El Sereno Stallions

Bobcats face tough La Canada Gladiators

ELAC Huskies take down San Jacinto College 31-13 www.wavenewspaper.com

Roosevelt holds on to beat L.A Jordan Bulldogs 44-25

F/S - Garfield 35..Bell 28

L.A. Roosevelt is given permission to wear black uniforms

» Kicks: APL’s One-Day BANiversary Event

Midget Div- East L.A Bobcats shut out Whittier Redskins

ELAC strikes late to beat Mesa .. wavenewspapers.com

Boyle Heights Splits two games a piece with East L.A

Roosevelt stunns Huntington Park in Overtime 27-21

Garfield beats L.A Jordan 35-21

The battle Continues , Boyle Heights Wolfpack vs East L.A Bobcats

Duarte runs past Hacienda Heights

Bobcats get thru Bell Gardens

jr midget div..Boyle Heights Wolfpack vs Arcadia Indians

peewee div- BH Wolfpack route Duarte 40-0

Garfield races past South Gate -thewavenewspaper.com

Al Davis dead at 82

F/S- South East Jaguars 38 ...Roosevelt 20

South East 42, Roosevelt 21...espnla.com

Steve Jobs Dies: Apple Chief Created Personal Computer, iPad, iPod, iPhone

South East's Garcia hailed as a hero

Cantu leads ELAC to upset of Antelope Valley

Robert Lewis puts South East on map

East L.A Bobcats go 3-1 vs Alhambra Thunderbirds

South East ends trying week with 31-28 win over Garfield

Roosevelt takes down South Gate Rams 22-14

F/S -Roosevelt 21... South Gate 7

Josh Quijada of Mater Dei vs Edison

Trial begins for Jacksons Doctor

College of Canyons victorious over Huskies

ELA Bobcats Defeat Huntington Park Spartans

St Paul 31 .. Garfield Bulldogs 8

Whittier Cardinals 21...Roosevelt Rough Riders 20

East L.A Bobcats Cage Lincoln Heights Tigers

ELAC Huskies dominate Glendale College 48-17

Boyle Heights Wolpack run past Huntington Park

Roosevelt holds on to beat Franklin 19-14

KLCS 2011 Eastern League Football Preview

South East RB Robert Lewis on NBC's "The Challenge"

Huskies suffer tough loss in Double Overtime vs St Monica College

East LA Bobcats Jr Midgets team to beat in 2011

Cathedral scores big on Banning Pilots

Roosevelt gets through L.A Wilson Mules 7-0

F/S - Riders kick mules 28-19

Edison 27 ..Garfield 7

The 5th Annual Community Awards Gala

L.A Valley beats ELAC Huskies 47-26

USC holds off Minnesota 12-9

Montebello Oilers get past Roosevelt 21-19

Bishop Amat squeezes by Garfield 14-0

Manuel Arts 21 Esteban Torres 6

JV - Montebello Oilers rally in 4th quarter to beat Riders 9-0

Josh Quijada scores three Touchdowns in Mater Dei debut

Nike presents - Gear Up or Shut Up

Arts District Los Angeles

Summer Night Lights 2nd Annual Bike Ride

Ride in Theatre - Self Help Graphics

the Red Album in stores August 23rd

Fiesta East Los

ELAC Green & White Scrimmage

Gold Shines for Roosevelt in Scrimmage

the new Pac-12

Compton Panthers defeat Moreno Valley Mercury 28-12

Latin American Basketball League @ Hollenbeck Youth Center

TC in Boyle Heights

Tweet by The Game jams L.A. sheriff's phone lines, delays deputies

Ride Metro -Silver Line /Green Line to the Harbor

Ricky Romero named AL Player of the Week

Man arrested after running more than a mile on Red Line track

Packers rookie Smithson prepared all his life for this role

Farmers Field Approved By Los Angeles City Council

Inglewood Blackhawks Football

Anthony Denham injures hammy

One return could change his life - Shaky Smithson

Dodgers snake D-Backs

Shaky Smithson, East L.A. College alum, signs with Packers

ELAC Huskies gear up for 2011 season

Hollenbecks National Night Out 2011

Blackhawks open season with 31-6 victory over the Compton Panthers

X-Games 17 in Los Angeles

Bryan Stow beating suspect allegedly assaulted 2 others

Leaving Los Angeles!

Father Boyle comes to Libros Schmibros Book Store in Boyle Heights

Pre Football Social with Coach Javier Cid & the Roosevelt Rough Riders

Zakee Johnson of Culver City High transfers to L.A Cathedral

David Mendoza -Spit the feelin- Deluxe Productions Music

Ricky Romero late addition to AL All-Stars

East Side Drum Circle 7-10-11

CicLAvia Community Ride 7-10-11

Concern Foundation's 37th Annual Block Party Fundraiser

Boyle Heights Farmers Market 1 Year Anniversary

Summer Night Lights @ Costello Park

El Sereno Independence Day Parade & Fireworks

4th of July Carnival @ Hollenbeck Park

Ground broken for new Garfield High Auditorium

Soul Skating LA's 1st Annual Sk8 & Create Board Art Exhibit

Garfield High School Alumni CookOut!

Critical Mass 6-24-11

Emerica Wild in the Streets Boyle Heights ,Los Angeles 2011

NoHo to Malibu / Venice Beach Bike Ride

L.A Wilson's Araujo City D-II player of year

Arts District Los Angeles

Boyle Heights Farmers Market

Inglewood Blackhawks on a Quest to defend title

Josh Quijada of the East L.A bobcats will attend Mater Dei High School

Ramona Gardens , East L.A Honor Noe Ramirez

Ex-Garfield linebacker headed to Arizona

Cal State Fullerton's Ramirez excited to join Sox

West is Best of the 605

Noe Ramirez's journey out of Hazard

Unearned runs cost L.A. Cathedral

Cathedral Phantoms baseball team advanced to the Semi-final round of Division-5 playoffs.

Memorial Day Service at Evergreen Cemetery

Memorial Day Honor & Salute - Los Cinco Puntos in Boyle Heights

L.A. Cathedral wins after 11-run seventh

1 arrest in Giants fan Bryan Stow beating, 2 others at large

Roosevelt Garfield Shine in Inner City Classic

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar shows small side ESPNLA

Inglewood Blackhawks tune up for 2011 season

Great Start for Ricky Romero: Blue Jays Beat Twins

Celebrate L.A Bike Week May 16-20

The Comedy "Food Stamps" Opens Reel Rasquache Art & Film Festival

Mister Cartoon putting it down!

"Food Stamps" Tha Movie -watch May 13th @ the 8th Annual Reel Rasquache & Film Festival

Boyle Heights' growing arts, music scene

Shaky Smithson Utah Utes Highlight Reel

MOCA's 'Art in the Streets' exhibition brings unwanted neighborhood effect: graffiti vandalism

Art in the Streets” @MOCA

Manuels El Tepeyac Cafe #2 Opens in City of Industry

Ricky Romero, Jose Bautista lift Jays by Yankees

Ricky Romero Web Gem Controversy

Dream+Act : film, videos and activism on immigration @ Self Help Graphics

Ghost Bike tie up for Manny Santizo

CicLAvia -Boyle Heights Committee hosts meeting at Corazon del Pueblo

FOX Sports Exclusive- Jays' Romero lives the American dream

Happy Birthday Momma 4-20-11

Clippers end season with win over Grizzlies, Blake Griffin hits Triple Double

CicLAvia April 10th 2011

Game featuring LiL Wayne "Red Nation"

Vigil Held For Dodger Stadium Attack Victim

Dodgers hire former LA police chief Bratton

CicLAvia set for April 10th 2011

Will-I-am on EG Entertainment talking bout the East Side

Ricky Romero fans seven in Opening Day win

Eastside councilman against $2-billion plan to raze sprawling Boyle Heights apartment complex

Confronting the challenges to Boyle Heights: health care, housing & harmony

Para Japón Con Amor - El Tepeyac Cafe raises money for Japans relief efforts

Opening Day 2011 Giants vs Dodgers

Softball :Garfield edges Roosevelt 3-2

L.A Dubb Car & Concert Show - 2011

Historic Boyle Heights Restaurant to Hold Fundraiser for Japan

Machete - A Brisk Story by Danny Trejo

Yo Soy Boyle Heights

Los Fearless by NIKE presents Ricky Romero of East L.A

East L.A Cityhood - March Madness Casino Night Fundraiser

Jose Huizar Beats Rudy Martinez in L.A. City Council District 14 Election:

Big League Dreams for the Lady Bulldogs of West Covina

LAPD has new system to help combat graffiti

Re-Elect Jose Huizar "Councilmen District 14"

Today is the 20th Anniversary of the Rodney King Beating

Inglweood Blackhawks hold 1st Tryout/Workout for the 2011 season

"Vote" Ozzie Lopez Candidate LACCD Board of Trustees Seat #1

Snider's regal path to Brooklyn started in Los Angeles

The Death of Ruben Salazar

All-Star NBA Jam Session in Los Angeles 2011

Los Fearless brings Basketball to Downtown Los Angeles

LA32 Neighborhood Council & The Voice Community News present Candidate Forum CD14

Garfield beats Roosevelt 19-12 in "1st Annual" Alumni Classic

Schurr spanks Montebello in Alumni Bowl 40-7

Councilmember Huizar Kicks Off Boyle Hotel-Cummings Block Restoration

Ronin Gray still on tha Grind with his new video "I Get Down"

"Boldly Boyle Heights" An Exhibiton of Photographs by Rafael Cardenas at Primera Taza

De'Anthony Thomas switches from USC to Oregon on signing day

Anthony Denham signs with the Pac 12 "Utah Utes"

Homeboy Industries Launches Chips, Salsa + A Food Truck

Garfield Bulldogs Alumni Football Practice 1-30-11

Snoop Dogg All-Stars Too Much for East L.A Bobcats

Polynesian All-American Classic 2011

S.I High School Player of the week DeAnthony Thomas of Crenshaw

ELA Bobcats remain undefeated beating Carson Gators 38-14

Will-I-am on Lopez tonight

Shaky & Fish Smithson

Josh Quijada of ELA Bobcats gets selected for San Antonio Eastbay Youth All-American Bowl

Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries Appears on "Dr. Phil"

Thomas leads Crenshaw to repeat performance

Fairfax crushes Chatsworth in Division II final

Boyle Heights Farmers Market- Virgen De Guadalupe

Small businesses find value in charitable giving , Aj's BBQ

USC gets Victory over UCLA 28-14

Football: L.A City Section championship schedule

Carson grounds Taft to reach City title game

Shaky Smithson makes the Scout/Foxsports.com All-America first team

Rave ban lifted at LA Coliseum, Sports Arena

Eastside Prep Football Teams Eliminated From Playoffs

Utah's Shaky Smithson makes 2010 All-Mountain West Football Second-Team

Could price of ride on Angels Flight get too steep?

Irish slip past Trojans 20-16

Carson comes out in 2nd half to beat Garfield 29-13

Salesian Boys & Girls Club of Boyle Heights/City Terrace Turkey giveaway

Jr Midget Div- Wolfpack lose to tuff Bell Gardens team in Championship

Inglewood Blackhawks win LCFL Championship over Vegas Kings

Midget Div- East L.A routes Whittier 56-6 to win Championship

Gremlin Div- East L.A falls to Glendora in championship

South East loses to Panorama City in double overtime 49-46

DIVISION I FOOTBALL PLAYOFFS BRACKETS

DVISION II FOOTBALL PLAYOFF BRACKETS

Gold Line Eastside Extension celebrates first anniversary of service

Inglewood Blackhawks return to LCFL West Championship

ELAC's Turner again defensive player of week

Huskies fall to San Bernandino Valley College

Jr Midget Div- Boyle Heights Wolfpack shut Out La Canada, head to Ship

Pee Wee Div -Bobcats lose in Shoot out to Asuza Raiders

Midget Division- East L.A Bobcats headed to ship by defeating West Covina Bruins

Bulldogs survive South East, 22-20

Roosevelt's new uniforms violated City rules

Jr Pee Wee Div- Duarte Hawks sqeak past Boyle Heights Wolfpack 6-0

East L.A Bobcats do it BIG in Playoffs

East L.A College Huskies roll past Compton College 34-8

Garfield beats Roosevelt in East L.A Classic 13-3

East L.A Classic Press Conference

I Voted 11-02-10

Jr Midgets - Bobcats beat El Sereno Sallions

Huskies hold on to beat Victor Valley College 26-21

Marxist Glue @ Hold Up Art

Women's Vollyball- Cerritos gets past ELAC 3-2

1 Dead in Boyle Heights School Bus Crash, Up to 50 Injured

East LA Bobcats & Boyle Heights Wolfpack split two games a Piece

South East comes back in Final minute to force OT against Bell & get 14-7 Victory

F/S in Overtime -Bell 28 South East 26

L.A Jordan 33 Southgate 14

Freshman- Alhambra 20 Schurr 6

Shaky Smithson solid for Utah

ELAC Huskies regroup & beat San Diego Mesa 30-7

St Paul 21 Cathedral 14

L.A Jordan Crushes Roosevelt 29-3

East L.A Bobcats Sweep Alhambra Thunder Birds

Inglewood Blackhawks Kill the California Dolphins 84-0

Shaky Smithson 293 total yards vs Iowa state

St Paul cruises by Schurr 42-7

F/S Garfield blows out L.A Jordan 56-6

ELA Bobcats Breeze through Huntington park Spartans

Huskies Offense just can't get it inn vs Antelope Valley College

Boyle Heights Wolfpack face tuff tests vs Rosemead & Bell Gardens

Riders get it done vs South East

Schurr holds off Cal High 28-23

JV Football- Bishop Amat rolls past Cathedral

Legislative Update on East Los Angeles CityHood -Town Hall Meeting

College of Canyons defeat ELAC Huskies 33-6

St Paul Stunns Garfield 24-10

East L.A Bobcats roll past Pico Rivera Dons

ELAC Huskies route Glendale College 33-13

Panthers finish off Riders 22-16

Mexican Independence Parade in East L.A

Huskies lose Heartbreaker 6-3 to St Monica

Shaky Smithson breaks out vs UNLV

Cantwell explodes on Schurr

Narbonne shuts out South East

JV -Orange Lutheran too much for Garfield

Huskies fall to L.A Valley 28-21

NBA Cares puts in new Basketball Court @ Salesian Boys & Girls Club in City terrace

Roosevelt lives on a prayer & gets past Alhambra 16-13

South East Shuts Out Eagle Rock 35-0

JV - Bishop Amat gets past Garfield

Inglewood Blackhawks defeated the Antelope Valley Vikings 57-13 (6-0 overall) 2-0 in League

East L.A College Green & White Football Scrimmage at its Best

Riders Compete with St Paul & Pomona High in Scrimmage

WaveNewspapers.com: Eastern League 2010 Preview

Summer Night Lights @ Ramona Gardens

Jr Midget Boyle Heights Wolfpack look to contend for a Title

East L.A Bobcats Football "Opening Day 2010"

Roosevelt Rough Riders Red & Gold Scrimmage 2010

East L.A Bobcats run past El Sereno Stallions -Midget Division Scrimmage Photos

Boyle Heights Wolfpack vs El Sereno Stallions "Flag Silver Scrimmage" Photos"

East L.A 2nd Annual Summer Festival & Car Show

Inglewood Blackhawks Shut out Desert Valley Knights 34-0

Boyle Heights National Night Out 2010

East L.A Bobcats first day of pads

East L.A College Football getting ready for 2010 Season

Inglewood Blackhawks go 4-0 in Preseason

Boyle Heights Neighborhood City Council Meeting 7-28-10

SB1070 Protest -Banners Drop from 1010 freeway -

Viva Las Vegas !!!

Sticky Ricks presents "Pelel Here 2010"

East L.A College Shootout Football Tournament

Blue Nation "Bully Expo"

El Sereno 4th of July Parade & Fireworks

Hollywood Park Horse Racing

Need Stickers? Stickyricks.net

Blackhawks kickoff of season with win vs San Diego Thunder 16-13

East Side Blike Club 2nd Year Anniversary BBQ

Garfield High School Classo of "72" Cook Out

East L.A College Football ready for 2010 Season

Lakers Championship Parade

Los Angeles Lakers Win NBA Finals

Mexico vs France - Nike - World Cup Soccer

Seeaca Cat Walk

NBA Finals - Lakers Win Game #1

Memorial Day Ceremony at Los 5 Puntos

El Sereno Celebrates Memorial Day

Ron with the Win

Lakers set Suns in Game #2

Bud Selig, Phil Jackson get it right on immigration law

Homeboy Industries lays off most employees as financial woes worsen

Utah Jazz @ L.A Lakers Game #2

May Day 2010

Critical Mass Bike Ride

Montebello High School 100th Year Anniversary

Fiesta Broadway 2010

Los Angeles White Supremacist Rally: LAPD Enters Tactical Alert At LA City Hall

Olvera Street businesses say rent increases may force closures

Obregon Park 2010 Youth Baseball Sign ups , space limited Register Now!!!

AJ's BBQ Pit one year Anniversary Celebration

Hard n da Paint featuring 2 MEX, NUAI, Sahtrye @ Selph Help Graphics

Asante new Carson grid coach

20 million people felt Mexicali earthquake; big aftershocks are 'likely,' Caltech says

Skid Row's Gladys Park Celebrates Easter in Style

Tweed Ride in Hollywood

Police Station in Boyle Heights Renamed, but not Without Controversy

East L.A College Huskies Women Softball defeat Mt Sac Mounties 12-10

Bobby Espinosa dies at 60; keyboardist for 1970s Latin soul band El Chicano

L.A. earthquake rattles region awake but no major damage is reported

Angels Flight, the 'shortest railroad in the world,' reopens in downtownL.A.

Former Dodger outfielder Willie Davis dies

Anaheim Dubb Concert & Car Show

After decades of neglect, the site where Chinese laborers were interred gets a memorial

Friends Aim to "Stand and Deliver" for Ailing Teacher

Boyle Heights celebrates its ethnic diversity

USC Athletic Director Mike Garrett opens up, just a bit

Bike club holds ride to celebrate Valentine's Day and friendship

Extending a hand to a faded East L.A. handball court

Club Cinespace in Hollywood , hosted by Eric BOBO , "Live " DJ GreenThumb, FunkDoobiest, DiS

C.E.O -Dayz of our Lives -Video

East Side Bike Club takes a trip through NELA

Cerritos balls up Lady Huskies

Power 106FM vs Salesian High Basketball

LAPD Chief Beck meet & greet at Salesian High school

Happy 50th Birthday Carlos Morales

R.I.P Coach- Carlos "Spanky "Huerta

nuAi - RISE N SHINE- video

Nike Presents 5 days til friday BCS Nation title Game at L.A Live - Conga Room

ELAC Huskies get past Compton College 66-61

Where is tha EastSide ?

Lady Huskies Fall to Mira Costa College Basketball

Utah Utes Beats Cal Bears 37-27 in Poinsettia Bowl

Jordan's Beck is coaches' pick for City player of the year

East L.A Bobcats vs Westside Jaguars "Bowl Game"

Asante resigns at L.A. Jordan

Hollenbeck Skate Park Plaza -Grand Opening-

Temple of Boom Studio

Hamilton - 2009 L.A City Division II Champs, defeat ECR 67 to 40.

Lakers Josh Powell stops by Salesian Boys & Girls Club Turkey Give Away

Clippers fall to Magic

Oaks Christian defeats Cathedral

Arizona’s Win Over USC Really Special for Schurr Product Diaz

Olmeca cd release party

Anthony Denham is a receiver on the rise -2009 Highlight Film-

USC 28 ..UCLA Football 7

Fairfax 24.Roosevelt 7

Beck leaves lasting impression on Pac-10 coaches

Smithson shakes off rough season

Ricky Rosas + Shaky Smithson nominated for FedEx Orange Bowl Courage Award

A good life: Ute Shaky Smithson shares good fortune with family

North County Cobras 25..Inglewood Blackhawks 23

Baseball: Poly hires ex-Roosevelt assistant

Schurr 14..El Rancho..7

Roosevelt 14..Grant 10

Narbonne Gauchos 33..L.A Jordan Bulldogs ..0

ELAC Womens Vollyball Defeat L.A Harbor

Schurr rides the arm of Cantu

Roosevelt draws No. 1 seed in City Div. II playoffs

Beck is Eastern League player of year

L.A City Section Division I- II pairings

Football: L.A City Section standings (FINAL regular season)

Metro EastSide Goldline Extension Grand Opening

Huskies Beat Santa Barbara in Overtime 52-46

East L.A Bobcats Playoffs Round 2

Roosevelt 20..South East ..6

East L.A Bobcats -1st Round Playoffs

Roosevelt Beats Garfield 28-16 to Win East L.A Classic

Coaches’ focus narrows in Classic

This rivalry is among friends

East L.A Classic -Press Conference 2009

Selph Help Graphics -Dia De Los Muertos

Inglewood blackhawks Shut out California Dolphins 42-0

Huskies Win Big over St Monica 51-37

Roosevelt Smashes Southgate 41-6

Metro EastSide Gold Line Extension Media Day

ELA Bobcats Route El Sereno Stallions

Antelope Valley College gets Past Elac Huskies

Boyle Heights Rec Center Soccer Fields in Full Use!

Roosevelt Shuts 0ut Bell 27-0

F/S- Southeast takes care of L.A Jordan

Pearson resigns at L.A. Roosevelt

Midget Div- Bobcats run past La Canada

Huskies beat L.A Valley in Shootout 41-40

Mini Classic - East L.A Bobcats vs Boyle Heights Wolfpack

Schurr comesback to beat Alhambra 28-21

Dodgers Beat Phillies in NLCS Game #2

JV - Bishop Amat 12...St Paul 6

Bobcats Beat La Puente Warriors

L.A Jordan comes up short vs Riders 14-12

Cantu leads Schurr over Whittier 24-7

East L.A College Mens Wrestling Defeat Rio Hondo College

ELA Bobcats Breeze Through Bell Gardens

Huskies give it away to L.A Pierce 35-27

Wolfpack look Good vs Alhambra T-Birds

Roosevelt Smashes Huntington Park

L.A Jordan ..7..Garfield..0

East L.A College Womens Vollyball Spike Trade Tech

Jordan Opens League Play Against Garfield

Jr Midgets-Rosemead runs Past Wolfpack

Huskies win Big vs L.A Southwest College 41-3

Whittier Stunns Roosevelt 28-21

JV..Roosevelt 27..Whittier 12

Roosevelt Is Unbeaten Thanks to Tough Defense and Strong Running

East L.A Bobcats vs Huntington Park Spartans

L.A. Roosevelt lineman is making noise

Pasadena College 49..East LA Huskies 27

Roosevelt 28...Contreras ..7

St Bonaventure beats L.A Jordan 42-21

Manny Ramirez Bobble Head @ Dodger Stadium

East L.A Mexican Independence Parade

ELAC Huskies 28..Glendale College 33

Glitches and finishing touches on Gold Line extension to East L.A.

Roosevelt 27...L.A Wilson 13

Freshman- ST Paul beats Garfield

JV -ST Paul 21...Garfield 16

Romero helps Rookie of the Year candidacy

Cerritos routs East L.A.

Eastern League Scores -Week 0

Roosevelt Wins Battle against Alhambra 34-20

L.A Jordan Runs Past Locke 25-0

JV-Scrimmage Pic's -Alhambra vs Roosevelt

ELAC Football -Green vs White Scrimmage Pic's

ELAC Mens Soccer- vs San Bernadino Valley College 2-2 tie

Riders Get Better in Red & Gold Scrimmage

Improved athleticism could lead to big leap for ELAC

Thunder Collins convicted of murder

Mike Beasley and His Twitter Just Made Life Harder for Himself

Ricky Romero gets 11th Win as Rookie

MEXICO vs URUGUAY Basketball Fight -Lorenzo Mata-Real Sighting

Inglewood Blackhawks Beat Valley Trojans 54-10

ELAC Football Practice Pictures 8-19-09

Primera Taza Coffee House "Grand Opening"

North County Cobras defeat Inglewood Blackhawks 13-6

East L.A Bobcats Opening Day vs Charter Oak

ELAC Football Practice pictures 8-14-09

Roosevelt Football Practice Pictures 8-13-09

Bobcats Run past Whittier Redskins in Scrimmage

I Love L.A -USC Style

Los Angeles Police Chief William J. Bratton to step down

Error may have freed suspect in Burk’s death

Boyle Heights National Night Out

AFL will cease operations

Summer Fest -True Memories Car Show - East L.A Whittier Blvd

Las Vegas, Sin City

Dorsey Beats Roosevelt in ELAC Huskie Shootout

East L.A. College hosts prep passing tournament

Crowd treated to a show at Fiesta Bowl

Inland Empire wins Fiesta Bowl

FIESTA BOWL: L.A. County players can sit back, relax

L.A. stars face tough test

Eastside Players Look to Lead L.A. County to Fiesta Bowl Win

Lakers sign Artest

Michael Jackson Memorial Service @ Staples Center

Ex Roosevelt Football Player Shot & Killed

GAME APOLOGIZES TO 50 AND EVERYONE AT INTERSCOPE

Ricky Romero takes no-hitter into seventh inning

NBA Draft 2009

Michael Jackson Dies at 50

L.A Lakers Championship Parade

Eastside Bike Club Ride to Staples Center

Coach Rick Gamboa's Pop Warner Youth Football Fundamentals Class @ East L.A College -Pictures

ELAC Football 2009-Practice

Kobe Bryant Best of All-Time ?

Laker fans near Staples Center Lued & Destroy Property

Lakers Win NBA Tiitle 2009...East L.A Celebration Whittier Blvd

Fisher Saves Game 4 ,for Lakers-East L.A fans go Crazy

Ghostbusters "The Video Game "

Lakers up 2-0 in NBA Finals

11 year old graduates from East L.A College

Lakers Beat Magic in Game #1

Youth Football Coaches Clinic @ East LA College this week 6-5/6-6

Lakers Win West

Eastside Goldline Extension Test Runs

WWE Smackdown @ Staples Center

Memorial Day- Raul Morin 2009

L.A Acura Bike Tour

Rapper Dolla is shot, killed at Beverly Center

Earthquake in Inglewood

L.A Clippers Win Big get #1 Draft Pick

Reel Rasquache Film Festival @ Cal state L.A

MannyWood gone for 50 games

Softball- Lady Bulldogs get Win vs Huntington Park

Garfield Beats Roosevelt 9-2

Softball- Spartans comeback on Riders 8-5

Fiesta Broadway Los Angeles

Softball-ELAC .4...L.A Harbor 0

USC wants more running backs

Dodgers Sweep Giants

Softball- Bulldogs Defeat Riders 9-2

L.A Dodgers Openinig Day 2009

A look at City Section Baseball league races

Romero has a dream debut

Ricky Has One More Letter & One More Win Than Rick

Narrowing In On Paths To Extend Gold Line Rails

Roosevelt's-Ricky Romero Wins Jays' Rotation Spot

Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa with Will.i.Am, Big Boy on Day of Service

Southeast Jaguars 4.. Roosevelt 7

Riders in Slump lose to Bell 11-4

Beck waiting on offer No. 1

Lady Bulldogs Beat Lady Riders 6-2

L.A Dubb Car Show

Bulldogs handle Riders first Loss 9-4

East Los Angeles receiver Antoine Smithson Commits to UTAH

Roosevelt Smashes Garfield Baseball

Lady Riders lose in Southern State Playoffs

Lady Riders Win Div 2 L.A City Championship against L.A Wilson 51-50

L.A Mayor gets Re-Elected

Latin American Basketball League

L.A Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa Campaign 3/1/09

Charlotte Bobcats Beat Clippers

JV Girls Basketball-Garfield Beats Westchester 56-47

6th Street Bridge design sparks clash in Los Angeles

Lady Riders Defeat Bell 52-39

Neighbors’ Hopes Ride High for Historic Shul’s Reviva

Jody Adewale will Play for Inglewood Blackhawks 09 Season

Lanny Delgado of Garfield underrated, and overlooked, by football recruiters

Ball State shows interest in Purvis

The buddy system helps in recruiting

Jordan Bulldogs Still Undefeated in Eastern League

Cathedrals Randall Carroll Still Undecided

South Hills QB makes decision

James Boyd to make announcement Feb. 1

Mark Sanchez Will Enter NFL Draft

USC Wins Rose Bowl

Big Man on Campus..Ricky Rosas

Allen Iverson "Reebok Old School Footage"

James Boyd Named L.A City Player of the Year

James Boyd named to USA Today's All-USA Team

Juanita O Robinson R.I.P

San Pedro, Narbonne share City title

Arleta 31.... Franklin 8 .... 3A L.A City Championship 2008

Franklin 13..Roosevelt.. 6

Roosevelt 25, El Camino Real 11

Birmingham wins rematch with Garfield

Nike- 5 Days 2 Fiday / Roosevelt Football

ELA Classic 2008

MaxPreps.com: Roosevelt, Garfield Meet in East LA Classic

This Classic will have title attached

East L.A. Classic could have feminine touch

Diaz is well-armed for success

L.A Jordan's Speed too Much for Garfield

L.A Coliseum appears out as City final site

Garfield Faces L.A Jordan

OBAMA Wins Presidential Election

Rickey Thenarse's New Home At Nebraska..(ESPN Video)

Huskies Get First victory over Santa Monica 42-37

Alhambra runs past San Gabriel 31-14

L.A Jordan Rebounds @ Southeast 53-14

Garfield Moves Past Huntington Park 22-7

Nike Presents five days to friday @ Dorsey High

Smart decision by coach Javier Cid

Roosevelt gives L.A Jordan a Rough Ride 33-21

Should USC call an audible with its incoming QBs?

James Loney stops by Roosevelt

Roosevelt Wins Close Battle vs Southeast 36-29

Inglewood blackhawks Back in LCFL Championship

Cyprees Hill Hip Hop Honors

Family affair for Sanchez brothers

Garfield Holds on and Beats Southeast 28-14

Oscar De La Hoya promotes hometown and next bout

Garfield Shuts out Bell 35-0

Riders get past Southgate 32-13

Roosevelt Football Locker Room Vandalized

Boyle Heights Wolfpack 20th Anniversary

Elijah Asante has Jordan High on the right track

Cathedral Alumni killed in Chinatown Hit & Run

Cathedral Smashes Contreras 62-0 in Home Opener

San Pedro 24 .. Garfield 3

New field will give Cathedral High's football team a fresh start

Mater Dei rallies past L.A. Jordan

L.A. Jordan wins while losing to Mater dei

Boyd sets state record in loss

James Boyd is a double threat for L.A. Jordan

Roosevelt's Javier Cid Coach of the Week

L.A Wilson Shocks Garfield 20-14

Anthony Denham is a receiver on the rise

County-USC prepares to replace its outpatient clinics

Eastern League Football Preview 2008

Roosevelt Comes Back and Beats L.A Wilson 21-20

James Boyd aka Bi-Polar Express

Dodgers Sweep D-Backs

San Diego Torrey Pines Shuts Out Roosevelt 41-0

Garfield Stunns Birmingham 29-28

Cain era begins at ELAC

These teams take tough road to top

L.A Jordan Faces Pre League PowerHouses

Roosevelt expects to go on the offensive against foes this year

Defending Invitational champ takes the physical approach

Press-Telagram: Eastern League Preview:

Inglewood Blackhawks Kill Cental Coast Grizzlies 84-0

A Day @ Universal Studios Hollywood

ELA Bobcats Scrimmage @ Cathedral

Garfield InterSqaud Team Scrimmage

Homeboy Industries

Alvarez hurls L.A. to RBI Senior crown

South East Senior could Surprise everyone in the City

X-Games @ Staples Center, Eric Koston & P-Rod

EarthQuake in Southern California

Boyle Heights Town Hall ends in Protest

David Lopez of Garfield High Got Hooked Up

Blackhawks Still Remain Undefeated & Beat L.A Generals 76-0

ELAC Nike ShootOut 7 on 7

Ricky Romero has Best Outing of the Year

Brittany Salsberry 's Reel

Blackhawks Beat Cal Long Horns

East L.A. Art center will need a New Home

Garfield moves up to top division

Speed kills City in L.A. Fiesta Bowl

Plenty of Southern Comfort at L.A Fiesta Bowl

Jordan's Boyd joins USC family and commits to the Trojans

NBA Draft 2008..OJ Mayo,Russel Westbrook,Kevin Love

Lakers Stay Alive in Game 5

Walls of L.A. River are a prime canvas for taggers

"Bucket" Arrested after YouTube Video

Roosevelt finishes quarter short in the City playoffs

Montebello Vet Killed 40 Years Ago, Still Waits for Final Resting Spot

ELAC’s Medwood state hurdles champ

City Council votes to save LA36 from budget cuts

Roosevelt's 11-run inning eliminates Taft in first round

East L.A. sends five individuals to state

City Section Baseball Playoffs

Alex Stepheson to Transfer Out of North Carolina

Garfield High School plans its new auditorium

East L.A. getting a long-overdue face-lift

Talk Radio with Roosevelt Head Coach Javier Cid - 2008

Former confidant says USC's Mayo received illegal benefits

L.A Avengers finish the Deal 66-59

MAY DAY RALLY

Lady Riders Defeat Bulldogs

Trojans Dominate NFL Draft

Garfield Upsets Roosevelt 5-3

L.A Jordan WR impresses at NIKE

Roosevelt makes it a rough ride for Eastern League opponents

Garfield @ Roosevelt Track & Field - 2008

Lady Bulldogs Defeat L.A Jordan

Gladiators Beat Avengers

USC Football Spring Practice Interviews

OJ Mayo Will Enter NBA Draft

USC Street Ball'n on Figueroa

Avengers Light Up Blaze

Jaguars Shut Out Bulldogs 1-0

Lunch with Laker Girls

NIKE Let Me Play

Roosevelt Sneaks Past Garfield 1-0

JV Bulldogs Beat Riders 16-6

JBL Basketball League

Roosevelt Powder Puff

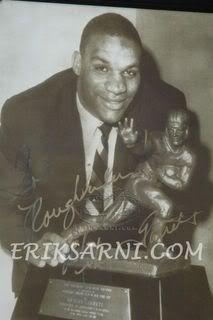

Frankie Diaz eriksarni.com Player of tha Year

Star of Clarkson QB Academy is a L.A. Wilson receiver

Roosevelt has an athlete with name to match his game

L.A Dodgers Back @ Memorial Coliseum

Pasadena @ East L.A College Softball

Tha Juice is Loose

NCAA Tournament

UCLA Wins Pac-10 Tournament

Sparks sign ex-Garfield great

USC gets visit from team mom

Villanueva Pitches No hitter against Garfield

Barrales Signs Deal With Fairbanks

Roosevelt Comes Back & Ties Palisades 6-6

Garfield Shuts Out L.A Wilson 8-0

L.A Bike Tour - L.A Marathon..2008

Upground , Casa De Calacas Perform @ QC 20/20

Thanks to Iloff, Huskies end season on positive note

Villanueva's journey has him back at Roosevelt

Family Issues Sent Rachal to the Pros

USC routs Beavers from the start

Moorpark 8 ELAC Baseball 6

Ronin Gray..Music "Boyle Heights"

Garfield Calls Out Birmingham

Nick Young Honored @ Galen Center

BRUINS Blackout Trojans

Mayo's mother gets up-close view

Knox joins Bruins recruiting class

L.A Jordan breezez by Garfield 74-42

Winning philosophy built on tough love

As long as there's hope, Mata-Real can cope

VOTE..2008

Eagles Soar over Riders 50-30

ELAC makes big plays at the end

An emotional custody dispute over history

Cerritos Defeats ELA College in Women & Mens basketball

L.A Wilsons Vic Cuccia Dies at 80

Towering ambitions for Boyle Heights - 2008

Plan to buy Sears site falters

Jody Adewale Ends USC Career with Rose Bowl Win

Rose Bowl 2008

New Years Eve Celebration with Joe Bataan, Tierra, Balance

ELAC turns to Cain to revive program

Miracle on 1st Street"KOBE BRYANT"

Southgate High Retires Lorenzo Mata -Real's Jersey - 2007

Garfield Beats University 28-23

Garfield Back in Championship

USC BEATS UCLA

Bulldogs’ Road to Finals Goes First Through Fairfax

Smithson's Versatility sets him apart

Open Letter From Mike Garrett

Turkey Bowl 2007

L.A City Semifinals

City playoffs round 2

Bulldogs get Revenge 31-13

Taft Slips past L.A Jordan

L.A City Playoff Pairings

Roosevelt Keeps Playoff Hopes Alive

Baby Bash -Power 106 @ Garfield High

Riders Pull UPSET 23-15

F/S ELA Classic - 2007

East L.A Classic 2007

L.A Jordan under City section Scrutiny

Lopez Drawing Recruiting Attention

Roosevelt comes up short against Spartans 21-27

L.A Jordan 42..Garfied 22 - 2008

Southeast Wins Azalea Bowl 32-20

Garfield shuts out Huntington Park 27-0

Garfield Rolls through Southgate 49-6

Stanford Upsets USC 24-23

Roosevelt 36..Southeast 57

F/S .RHS Shuts Out Southeast -2007

Bell..3.. L.A Jordan 51

Boyd double trouble for Huntington Park

Its a Family thing for Garfield Standout

Southeast High in the News

Garfield Cruises by Southeast 28-7

San Pedro Slips Past Garfield..14-7

Huskies 21..L.A Harbor.26

Bulldogs hold lead and Defeat L.A Wilson 21-14

F/S..WHS.7..GHS..22

Dodgers Win in 12th

T.V Show Intros

Stafon Johnson makes his Move

Viva Las Vegas

Ryan Francis Killer gets LIFE - 1/25/08

C-Webbs BadaBling Party

Bulldogs Win ELAC Shootout

City Beats Cif...22-12

Old memories Car Show 6/17/07

Avengers win Big

NBA DRAFT O7

Capturing An Historic Moment on Metro Gold Line

Justin A. Verdeja killed in Iraq

Student Arrested in Garfield High Blaze

Oscar De La Hoya Donates $50,000 to Garfield High

Damon Wheeler comes back Strong for Avengers

Garfield will Rebuild Auditorium

Lady Bulldogs Come Up Short in Finals ,Due to Bad Call by Lady Umpire

Avengers win close Game

E.L.A Skate Park Finally Opens

Fire Destroys Garfield High

Roosevelt Beats Huntington Park 10-3

WALK OUTS

LAPD Brutality @ Mcarther Park

O.J Mayo Highlights

Abdoulaye N'diaye Exit Interview

No Limit Soldier Enlists at USC

Nick Young will enter NBA Draft

"Opening Day" at Ballpark no Picnic

OJ MAYO Eager to Join USC - 2007

Young carries memory of Francis

RYAN FRANCIS ..r.i.p

LODRICK STEWART....usc